by Fatema Al Majed January 24, 2021

Female citizens of Bahrain married to foreigners demand citizenship for their children

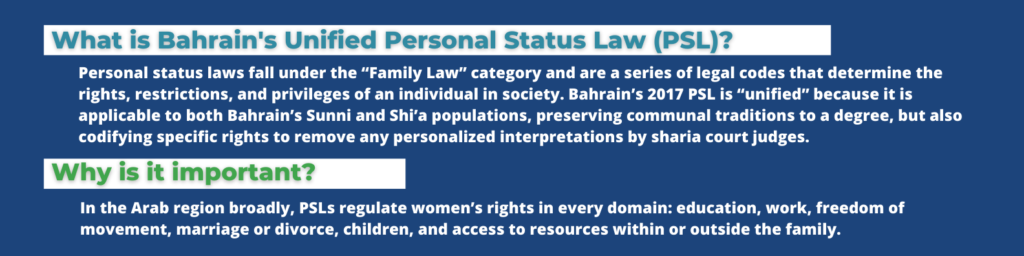

Through its Strengthening Implementation of the Personal Status Law in Bahrain program, PartnersGlobal focuses on the citizenship topic as one of several areas for improvement in the implementation of the personal status law

This article was originally published in Arabic by Raseef22. The English version below has been edited for clarity.

There are many questions that Bahraini women who are married to foreigners carry as a weight on their shoulders, which raise certain fears for their future.

This anxiety overtakes their hopes, and their lives begin to seem like open-ended stories. These women are in constant search for answers to their endless questions and their children are in constant search for identity. It is an identity that they know very well but that does not officially belong to them or appear in their documents, even though they feel it in their sense of belonging, dialect, and customs!

Apprehensions around residence permits of a foreign husband and children

Shaikha, one such woman in this position, tells Raseef 22:

“The future worries me, for a person could die any time, and I can’t help thinking: ‘What will my children do after my death? How will they remain in Bahrain?’

I currently do not face any financial difficulties due to my good financial situation and my position at work, but I cannot help thinking about my children’s residency in Bahrain after they exceed the legal age as I will not be able to sponsor their stay after they exceed the legal age. So, what will happen if my son does not find a job after completing education? Will he be deported? Should they find a job, will they be treated as foreigners in the only country they have known?”

Shaika’s suffering started 13 years ago when she married a Moroccan man. Although Bahraini law allows Bahraini men to sponsor (citizenship for) their foreign wives, this does not apply to Bahraini women married to foreigners.

“My fears started to grow after I had my kids,” Shaikha says. “Will my kids be able to inherit my house if I died? Today foreigners are allowed to own property only in investment areas and my house is situated in a residential area. Will my children’s rights to the house be acknowledged?”

She continues: “I have been able to overcome many situations but there are many more to come. For instance, at the beginning of my marriage I received the electricity bill, which had not been paid by the government as it should be for Bahraini citizens. I went to the authorities with complete certainty that it must be some sort of mistake, for I am a Bahraini citizen, and the lease agreement is under my name, and it is my right that the electricity should be supported by the government! The employee working there told me, “The word ‘citizens’ refers to male citizens!”

No right to housing, no accommodations

“I feel helpless, and my children’s basic rights have turned into unattainable dreams for me.”

This is how 27-year-old M.A.H (who chose to be referred to by her initials for this story) describes her situation. She dreams of enrolling her 5-year-old daughter in nursery school. However, financial difficulties stand in her way.

In a voice filled with pain she says, “The suffering I am going through is bigger than me finding words to describe it. I am a mother of two girls, the eldest is five and the youngest is one and a half. I am married to a Pakistani man. He had applied for citizenship in 2006 and is still waiting. I am worried that my children’s future will be like their father’s, especially since the law today prioritizes Bahrainis. We do not receive help from the government in terms of financial support, employment, or unemployment.”

She adds: “I am facing family issues with my husband’s family, and we do not have a place to live. So, my family and I keep moving from one place to another without any source of income, for my husband is currently unemployed and is ineligible to receive unemployment from the Ministry of Labor and Economic Development because it is only given to Bahraini citizens, even though his mother is Bahraini! I borrow money every time his residence permit is due for renewal and I live on the charity of others that may or may not come! So, I wait and worry!”

Citizenship application requests stopped for an unknown period!

M. points out that she submitted an official application request for her 5-year-old daughter with the Nationality, Passports and Residency Affairs by filling out the application forms, attaching the birth certificate, the Bahraini mother’s passport, a letter from the mother, as well as an official paper showing that the children are in the custody and sponsorship of their Bahraini mother. Yet there is no specified timeframe for her to get an answer to this request.

As for her second daughter, the mother learned that the window for submitting citizenship applications is currently closed for an unknown period due to the coronavirus.

She explains: “Following up on the matter has become difficult, and the wait has become terrifying because it means that my daughter will wait longer until she is granted citizenship. These requests take a very long time, and I am afraid that she will reach the legal age without a citizenship and then be trapped in this dilemma of solving her residency.”

M. continues: “I feel that everything in life is against me. I even requested financial aid from the authorities that provide financial support to low-income citizens, and my request was rejected because I am married to a non-Bahraini.”

She concludes by saying that she still tries communicating with the relevant authorities from the Royal Court to the Supreme Council for Women as well as all the civil women associations with no solution whatsoever!

Amending the law to be in line with the Bahraini Constitution

Article 4 of the Bahraini Nationality Law of 1963 states that a person is considered a Bahraini if he was born in Bahrain or outside Bahrain and his father was a Bahraini at the time of his birth. It is also possible to apply for citizenship upon fulfilling a set of conditions set forth in the law itself.

In 2017, The Committee of Foreign Affairs, Defense and National Security in parliament rejected two proposals for a law aimed at granting nationality to the children of a Bahraini mother married to a foreigner, explaining that “the issue of granting Bahraini nationality is related to the state’s sovereignty, which does not require expanding the grant of the citizenship without restrictions.”

In this context, Mariam Al Rowaie, an activist in the field of women’s rights and empowerment, says: “The fundamental solution to this issue is to amend Article (4) of the Bahraini Nationality Law to be in line with the spirit of the Bahraini constitution, which stipulates and affirms equality between women and men.”

Regarding temporary solutions for this matter, Al-Rowaie – who is a member of the Nationality Committee of the Bahrain Women’s Union and the head of the Tafawuq Consulting Center for Development – stated that it is possible to take measures to treat the children of Bahraini women equally when it comes to Bahraini citizenship. She pointed to the issuance of Law 35 in 2009 requiring that non-Bahraini wives married to Bahraini citizens and children of Bahraini women be treated the same as citizens in the fields of education and health. However, there are some loopholes and is not effectively implemented.

Al-Rowaie continues in her interview with Raseef22: “The children of Bahraini women are still deprived of scholarships. There is a woman whose son’s average exceeded 98 percent, and he did not obtain a scholarship. These children do not fully benefit from health services like the rest of the citizens, and their residency in the Kingdom is temporary and not permanent.”

Until the law is amended, Al-Rowaie demanded real solutions that end or alleviate their suffering, such as issuing a card that qualifies children of Bahraini women to benefit from privileges in employment, housing, social insurance, and residency.

Efforts of governmental and civil institutions

More than ten years ago, the Supreme Council for Women in the Kingdom of Bahrain launched a service to follow up on citizenship requests for the children of Bahraini mothers married to foreigners after these requests are submitted to the Nationality, Passports and Residency Affairs at the Ministry of Interior. The service seeks close out the requests with relevant authorities and expedite the acquisition of citizenship for these children.

In 2005, the Bahrain Women’s Union launched a campaign called, “Nationality is a right for me and my children.” The ongoing campaign activities include holding educational and awareness events, sharing information through media and social media, and meeting with members of parliament and with the Supreme Council for Women.

Children without citizenship and rejected requests

In one of the seminars organized by the Bahrain Women’s Union, Muhammad Ghulam, the son of a Bahraini woman who married an Iranian and separated from him a year after she gave birth, said, “I lived all my life with my mother in my grandfather’s house, and I do not have any nationality. I married a Bahraini woman, and we had our first child, and now my child is suffering from what I suffered because she is like me. She also is without a nationality!”

Nedaa Ali recounted her story in the same seminar. Some parts of the story were shared with Raseef 22.

She says, “I am a Bahraini citizen who married a Pakistani man and gave birth to three children born in Bahrain. Then my husband died. I have knocked on the doors of the Ministry of Housing more than once for being a widowed citizen, unemployed, and the sole breadwinner of my family, but my application was rejected because the children are non-Bahrainis.”

Zahra Salman narrates her story at the same seminar, stating, “I married an Iraqi man 37 years ago, and when we wanted to settle in Bahrain, I was unable to sponsor him back then and today he must be registered as an employee. Now that he has reached the age of sixty, we are facing difficulties in renewing his residency because of a law that stipulates that expatriates over the age of sixty can only renew their residency if they are in specialized occupations.”

She adds, “As for my children, I cannot sponsor them because they are over the age of eighteen and face difficulties in acquiring residency. I also have a daughter who is married to an Iraqi citizen, and I suffer greatly whenever we try to issue a visit visa for her.”

These are the voices that we were able to hear, but there are many others that we could not reach. Whenever we hear a story, we say that it’s terrible, and then we hear of greater suffering. The suffering grows and multiplies, and only the questions and confusion remain.

We wonder and search for solutions. We want to know how granting citizenship to the children of Bahraini women will affect the state’s sovereignty. What are the obstacles coming between granting the children of Bahraini women permanent residency? How long will these voices continue calling and remain unanswered?