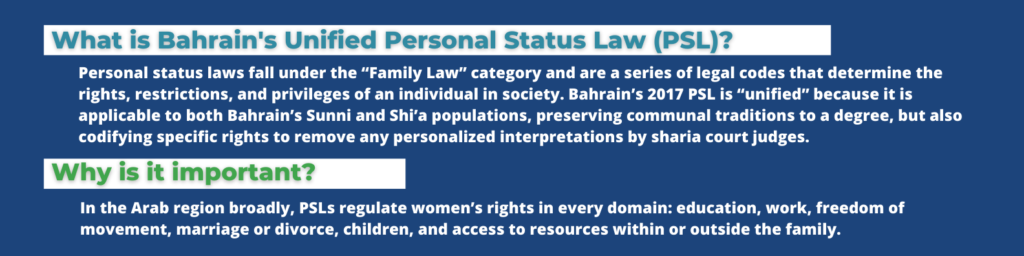

A small island situated in the middle of the Persian Gulf, the Kingdom of Bahrain is touted as one of the most progressive countries in the Middle East for women’s equality and advancement. It is a diverse and more religiously liberal country in comparison with some of her neighbors. Legally, Bahraini women are recognized in the Bahraini Constitution as equal to Bahraini men in “political, social, cultural and economic spheres of life, without prejudice to the provisions of the Islamic Shariah.” Bahrain is also a member of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and in 2017, adopted the unified Personal Status Law (PSL – known also as the Bahrain Family Law) – an important step in the protection of both Sunni and Shi’ite women under an inclusive legal framework, following trends in the region. Throughout 2020, the Supreme Council for Women took measures to protect these advancements and mitigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Persistent Challenges for Bahraini Women

Despite the gains made in the past 20 years, systemic barriers to women’s legal equality and empowerment continue to exist. For example, Bahraini citizenship for children is determined by the citizenship of the father. Bahraini women who are married to non-Bahraini men cannot pass their citizenship onto their children, leaving their children effectively stateless and without legal protection.

Some barriers were exacerbated by the restrictions put in place to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus. For instance, due to mandatory lockdowns and curfews in Bahrain, victims of domestic abuse were forced to reside with their abusers for long stretches of time. One such woman—who for security reasons will remain nameless—wished to obtain a divorce due to domestic abuse she was suffering during the pandemic. However, in Bahrain it is difficult both legally and culturally for a woman to divorce a man, including due to domestic violence. Legally, when a woman files for a divorce due to abuse, the process requires this same woman to first provide proof of the abuse or harm; her word alone is not sufficient. Therefore, women who are subjected to violence—including the woman mentioned here—are forced to first file a police report and a obtain a medical report, following a medical examination, to prove the harm in court. Additionally, the pandemic has delayed court hearing processes and prevented lawyers from meeting with clients.

Culturally, domestic violence is seen as a household issue. There is no official database with domestic violence statistics in Bahrain. The stigma around reporting domestic violence exists, dissuading anyone from formally moving forward with the process. A man, on the other hand, can submit a request for divorce without even informing his wife and without any cause.

An Opportunity to Advance Further Legal Reforms

Adopting the unified Personal Status Law in 2017 was a positive step towards women’s equality in Bahrain. Yet there are still improvements to be made, as was revealed by the impacts of the pandemic. Women-led local civil society organizations (LCSOs) are in the driver’s seat and are demanding further reforms. Since 2019, Bahrain’s women-led local civil society organizations have taken the lead on drafting amendments to the unified Personal Status Law and, in December 2020 they finalized a list of amendments to ultimately be presented to the Bahraini parliament for adoption in the future.

In the coming months, these LCSOs will launch a series of advocacy efforts aimed at the amendments’ adoption. This will begin by publishing the proposed amendments and meeting with relevant Bahraini authorities. The work of Bahraini women civil society leaders in the context of shrinking civic space demonstrates the power of long-term, collective efforts. The persistence, resiliency, and determination of this group drive the transformative change for a more inclusive, equitable, and prosperous society.